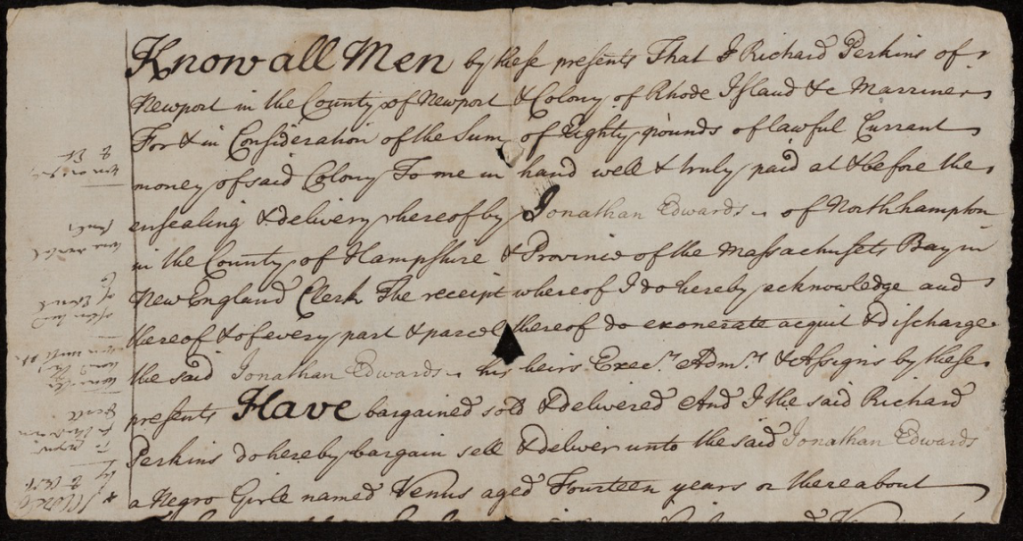

As mentioned in the latest post Slavery in Northampton, the town’s minister Jonathan Edwards went to Newport, Rhode Island and purchased an enslaved young girl. Historic Northampton generously shared a copy of the topmost part of the bill of sale for the “Negro Girle named Venus” dated June 7,1731. Edwards, years later, cut the receipt into three strips and used the back for notes for a sermon. Used here with the permission of the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale University. Transcription below the photo is by the Jonathan Edwards Center at Yale University, New Haven CT.

KNOW ALL MEN by these presents That I Richard Perkins of Newport in the County of Newport & Colony of Rhode Island &c Marriner For & in Consideration of the Sum of Eighty pounds of lawful Current money of said Colony To me in hand well & truly paid at & before the ensealing & delivery hereof by Jonathan Edwards of Northampton in the County of Hampshire & Province of the Massachusetts Bay in New England Clerk The receipt whereof I do hereby acknowledge and thereof & of every part & parcel thereof do exonerate aquit & discharge the said Jonathan Edwards his heirs Execrs Admrs & Assigns by these presents HAVE bargained sold & delivered And I the said Richard Perkins do hereby bargain sell & deliver unto the said Jonathan Edwards a Negro Girle named Venus aged Fourteen years or thereabout TO HAVE & TO HOLD the said Negro girl named Venus unto the said Jonathan Edwards his heirs Execrs & Assigns and to his & their own proper Use & behoof for Ever AND I the said Richard Perkins do hereby for my Self my heirs Execrs & Admrs covenant promise & agree to & with the said Jonathan Edwards his heirs Execrs Admrs & Assigns by these presents That I the said Richard Perkins at the ensealing & delivery hereof have in my own Name good Right, full Power & lawfull Authority to bargain sell & deliver the said Negro Girl named Venus unto the said Jonathan Edwards in manner & form aforesaid And shall & will warrant & defend the said Negro Girle named Venus unto the said Jonathan Edwards his heirs Execrs Admrs & Assigns against the lawfull Challenge & Demand of all manner of Persons whatsoever Claiming or to claim by from or under me or otherwise howsoever IN WITNESS whereof I the said Richard Perkins have hereunto set my hand & Seal the Seventh day of June in the Fourth Year of the Reign of our Soveraign Lord George the Second by the grace of God of Great Britain France & Ireland King Defender of the Faith &c

Anno Dm 1731

Richd Perkins

Sealed & Delivered in the presence of us

John Cranston

Jas Martin

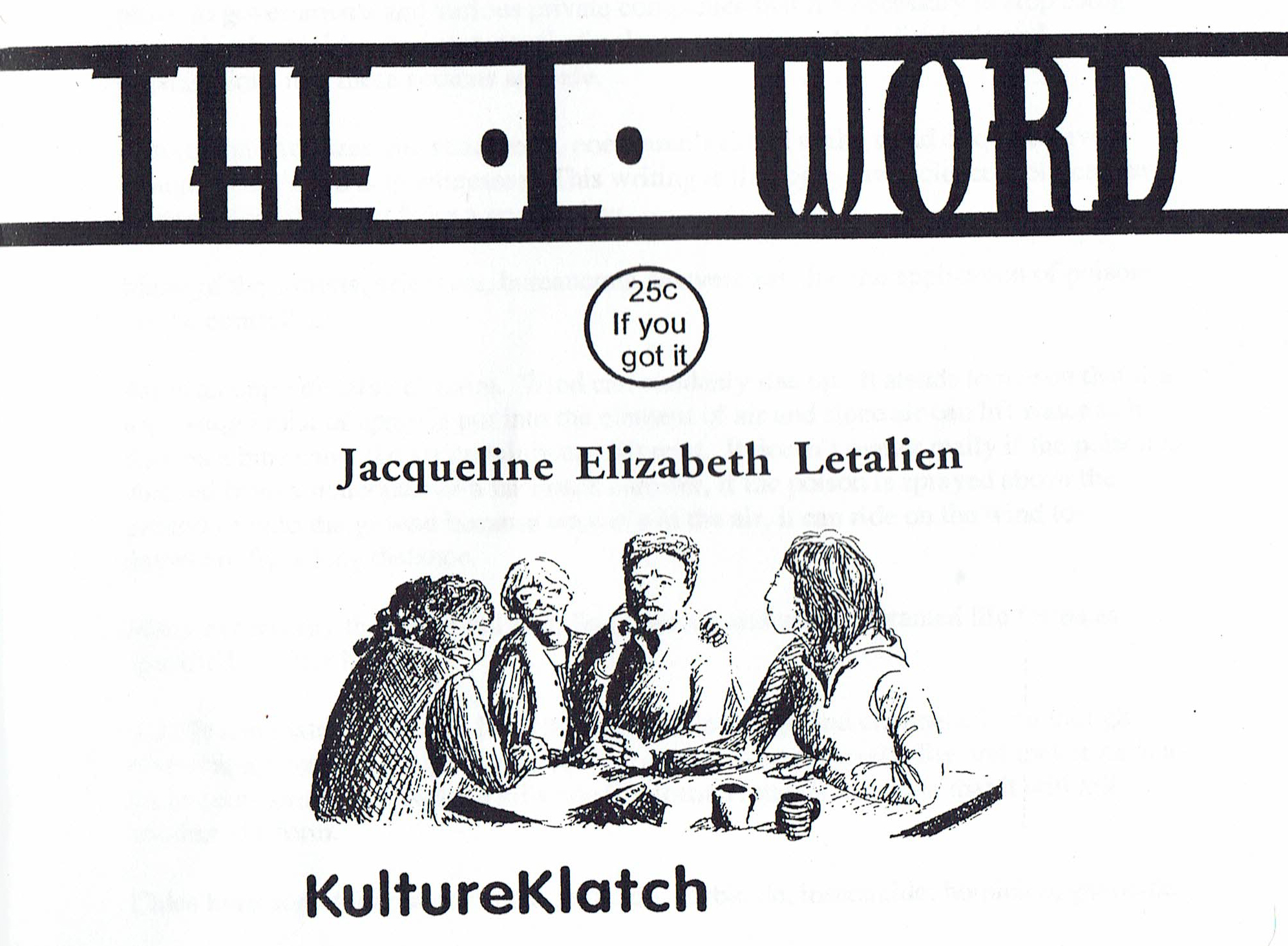

Valley Women’s Voice Oct. 1982

Valley Women’s Voice Oct. 1982 Gay Community News. Boston, MA. Feb. 12, 1983

Gay Community News. Boston, MA. Feb. 12, 1983 flyer vigil Feb 8, 1982 Northampton, MA

flyer vigil Feb 8, 1982 Northampton, MA

Daily Hampshire Gazette, Northampton MA and UMass/Amherst Massachusetts Daily Collegian coverage Oct. 23, 1978

Daily Hampshire Gazette, Northampton MA and UMass/Amherst Massachusetts Daily Collegian coverage Oct. 23, 1978

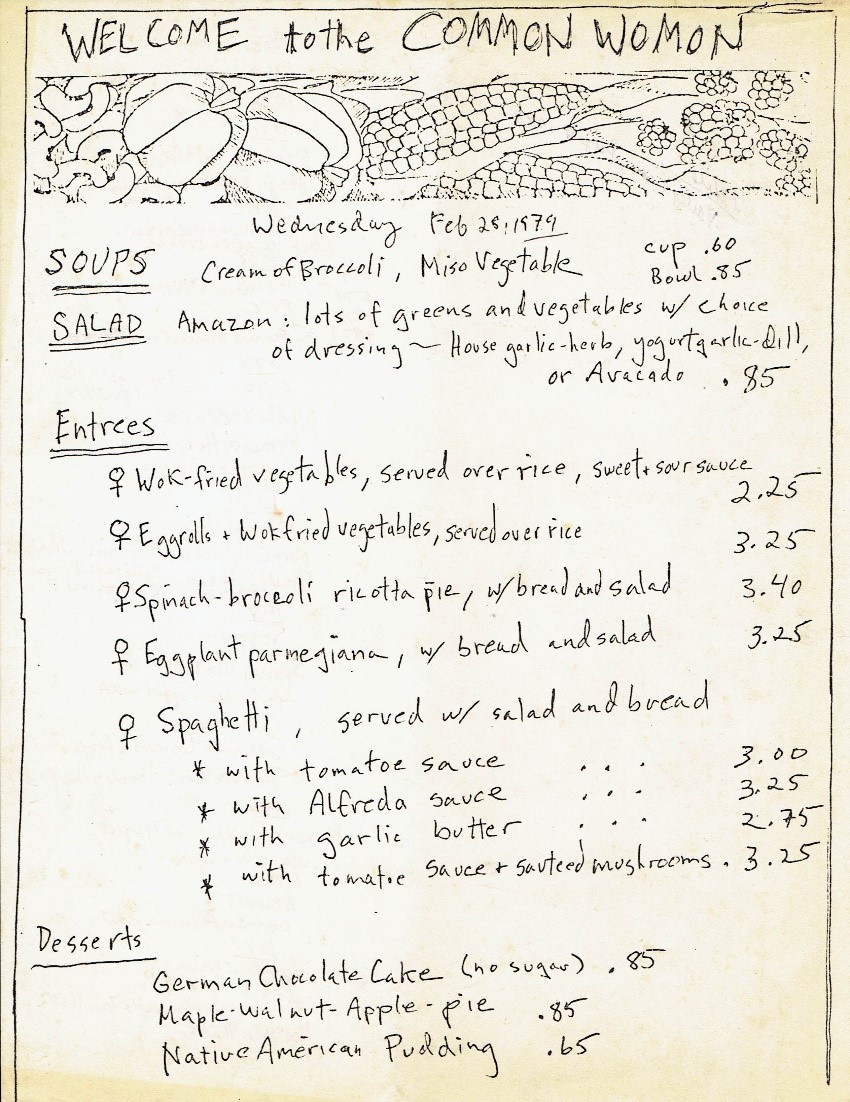

Springfield (MA ) Union Oct. 24, 1978

Springfield (MA ) Union Oct. 24, 1978

Springfield Union Nov. 1, 1978.

Springfield Union Nov. 1, 1978.

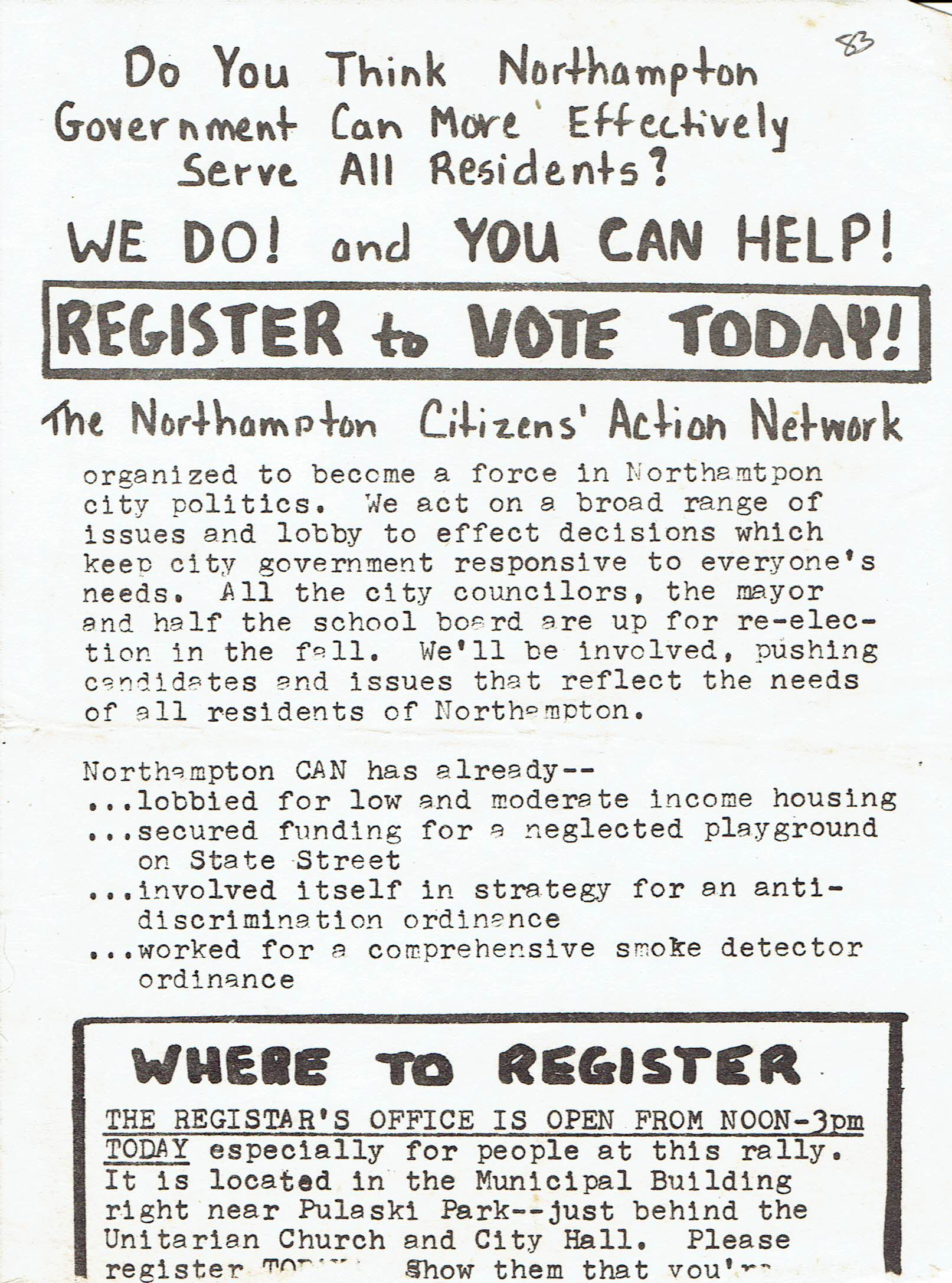

Flyer distributed Nov. 5, 1978, mimeograph one of two sides, courtesy Bambi Gauthier

Flyer distributed Nov. 5, 1978, mimeograph one of two sides, courtesy Bambi Gauthier

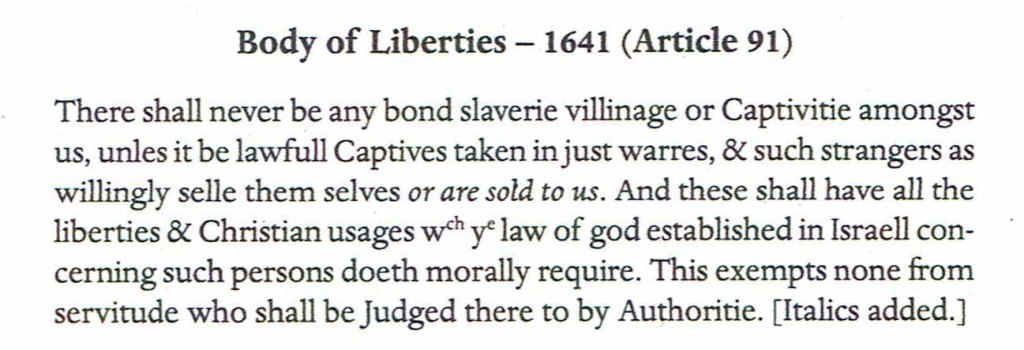

Springfield Republican Nov. 4, 1978.

Springfield Republican Nov. 4, 1978.

Laura Kaye watercolor of the Gala Café (Bridge St. Northampton) 1981, commissioned by Mary Vazquez, used by permission of both.

Laura Kaye watercolor of the Gala Café (Bridge St. Northampton) 1981, commissioned by Mary Vazquez, used by permission of both. Notice in the Women’s Media Project newsletter Jul/Aug 1978

Notice in the Women’s Media Project newsletter Jul/Aug 1978

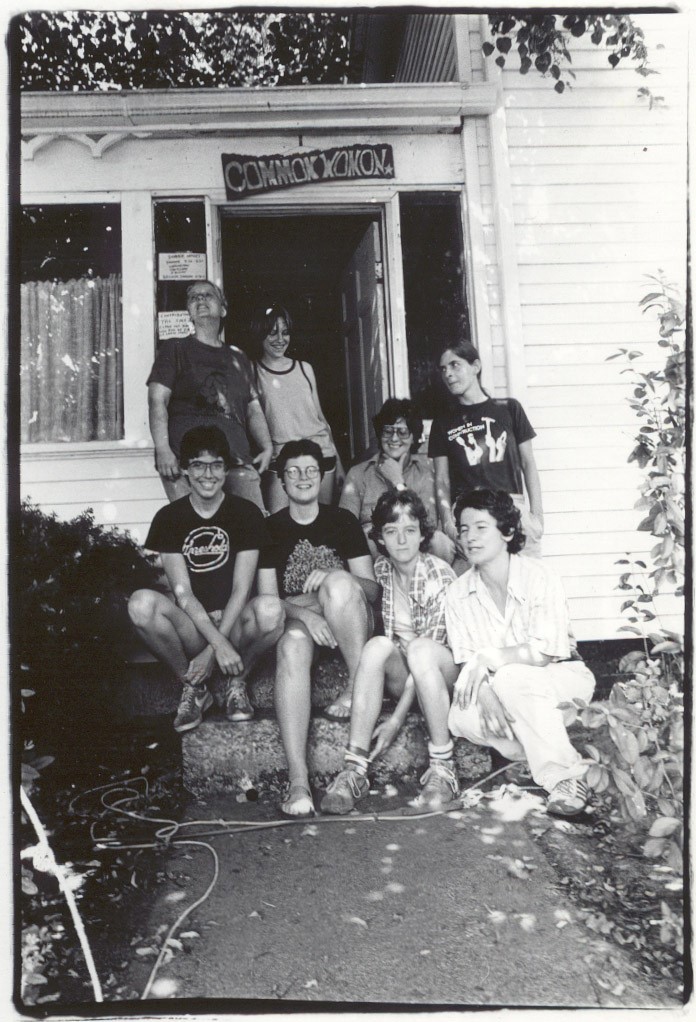

Ad in Fresh Ink, Mar. 8, 1979

Ad in Fresh Ink, Mar. 8, 1979

As reported in

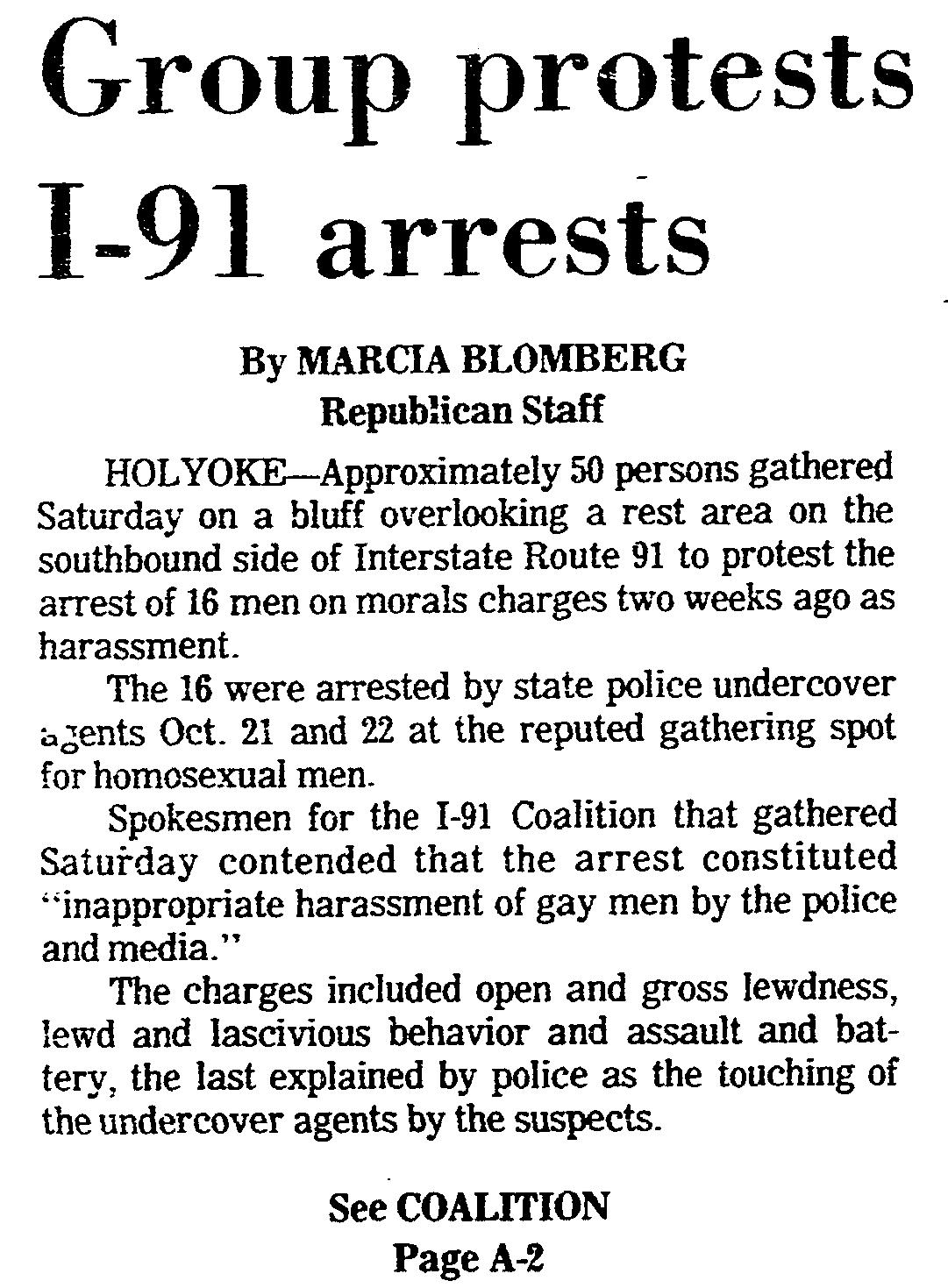

As reported in  1977 Common Womon Club initial policies, handout for members.

1977 Common Womon Club initial policies, handout for members.

This part of the article in the Springfield Republican Apr 24, 1977 really got the food described. Jan Whitaker discovered that this coverage was further circulated by the UPI wire service and reprinted in various forms in sixteen mainstream papers across the country and into Canada. In a story published a year later in the Republican Collective members expressed their belief that mainstream coverage had focused on an alleged anti-male bias and, as a result, in interviews asked that their last names not be used.

This part of the article in the Springfield Republican Apr 24, 1977 really got the food described. Jan Whitaker discovered that this coverage was further circulated by the UPI wire service and reprinted in various forms in sixteen mainstream papers across the country and into Canada. In a story published a year later in the Republican Collective members expressed their belief that mainstream coverage had focused on an alleged anti-male bias and, as a result, in interviews asked that their last names not be used.

LC Dec 77

LC Dec 77

Photo and artwork copyright Elizabeth Samit a member of the Hestia Mural Collective, used by permission

Photo and artwork copyright Elizabeth Samit a member of the Hestia Mural Collective, used by permission

1973 poster layout by Kaymarion [Raymond]

1973 poster layout by Kaymarion [Raymond] Springfield Women’s Center Newsletter Mar. 21 1973

Springfield Women’s Center Newsletter Mar. 21 1973

Undated and Unattributed clipping, likely April 1975 Springfield Union.

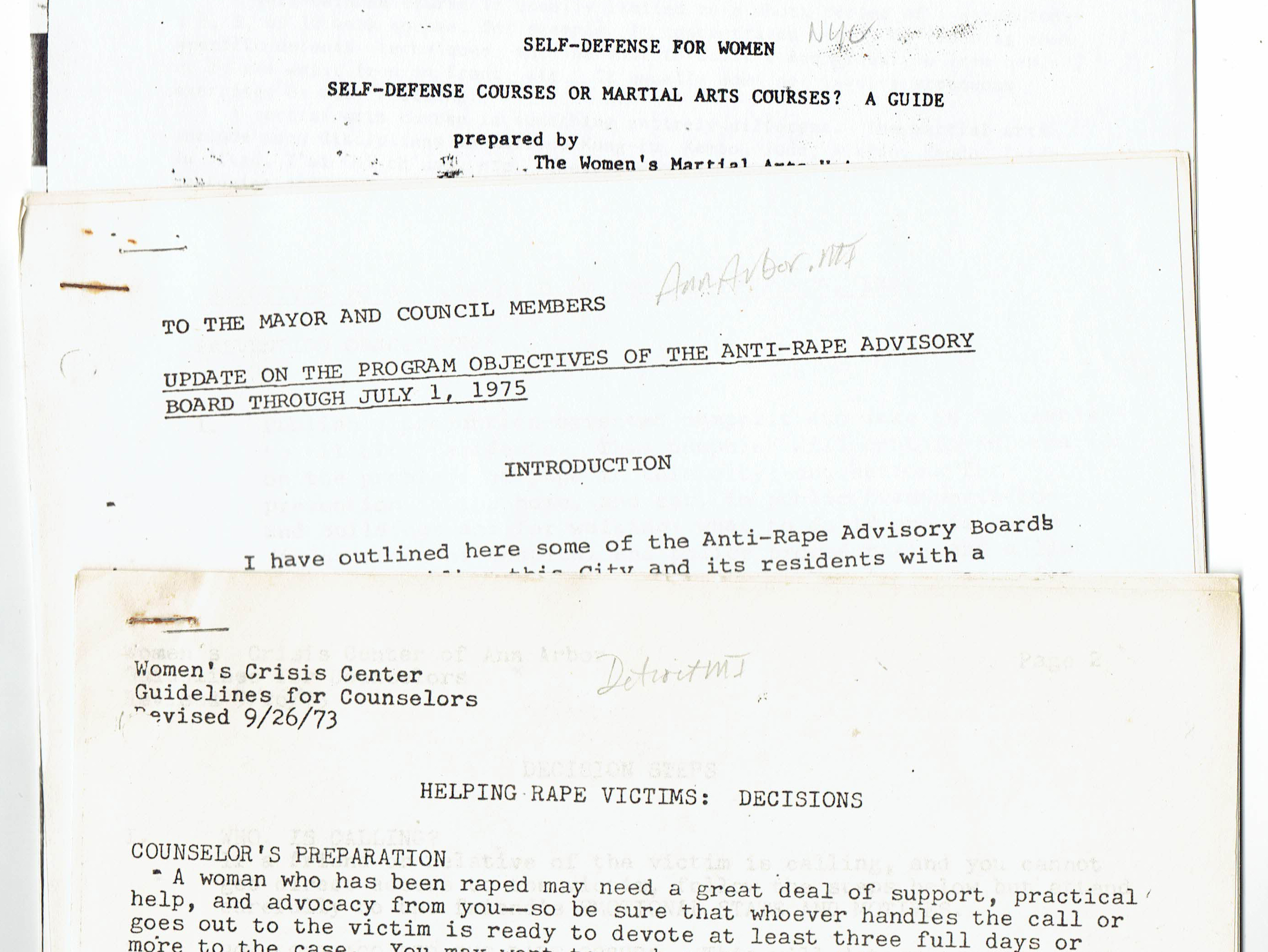

Undated and Unattributed clipping, likely April 1975 Springfield Union. Springfield Rape Crisis Center brochure undated

Springfield Rape Crisis Center brochure undated From Dyke Doings Nov. 1976

From Dyke Doings Nov. 1976 Undated [May 14, 1976?] and unattributed publicity for Anti-rape March

Undated [May 14, 1976?] and unattributed publicity for Anti-rape March

“Pat Turney and Cindy at Training Camp “, photographer unknown. Courtesy of Cindy

“Pat Turney and Cindy at Training Camp “, photographer unknown. Courtesy of Cindy

mimeographed songsheet first Take Back the night March

mimeographed songsheet first Take Back the night March Springfield Union Nov. 6 1978

Springfield Union Nov. 6 1978

First issue of Dyke Doings mimeographed newsletter Sep-Oct 1976

First issue of Dyke Doings mimeographed newsletter Sep-Oct 1976 Valley Women’s Union handout, undated [early 1977]. Unknown artist.

Valley Women’s Union handout, undated [early 1977]. Unknown artist.

Massachusetts Daily Collegian, student paper UMass Amherst, Oct. 1971

Massachusetts Daily Collegian, student paper UMass Amherst, Oct. 1971

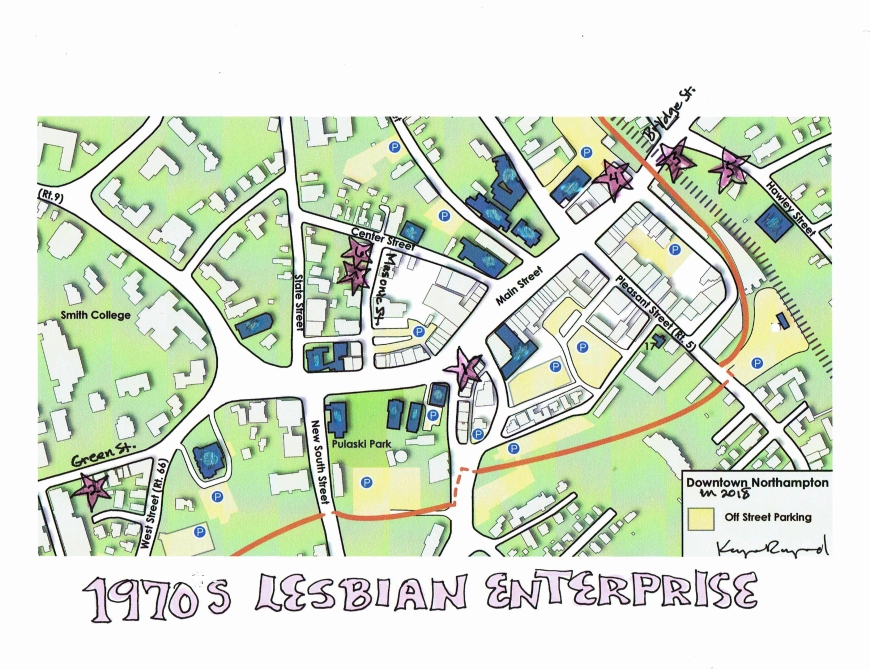

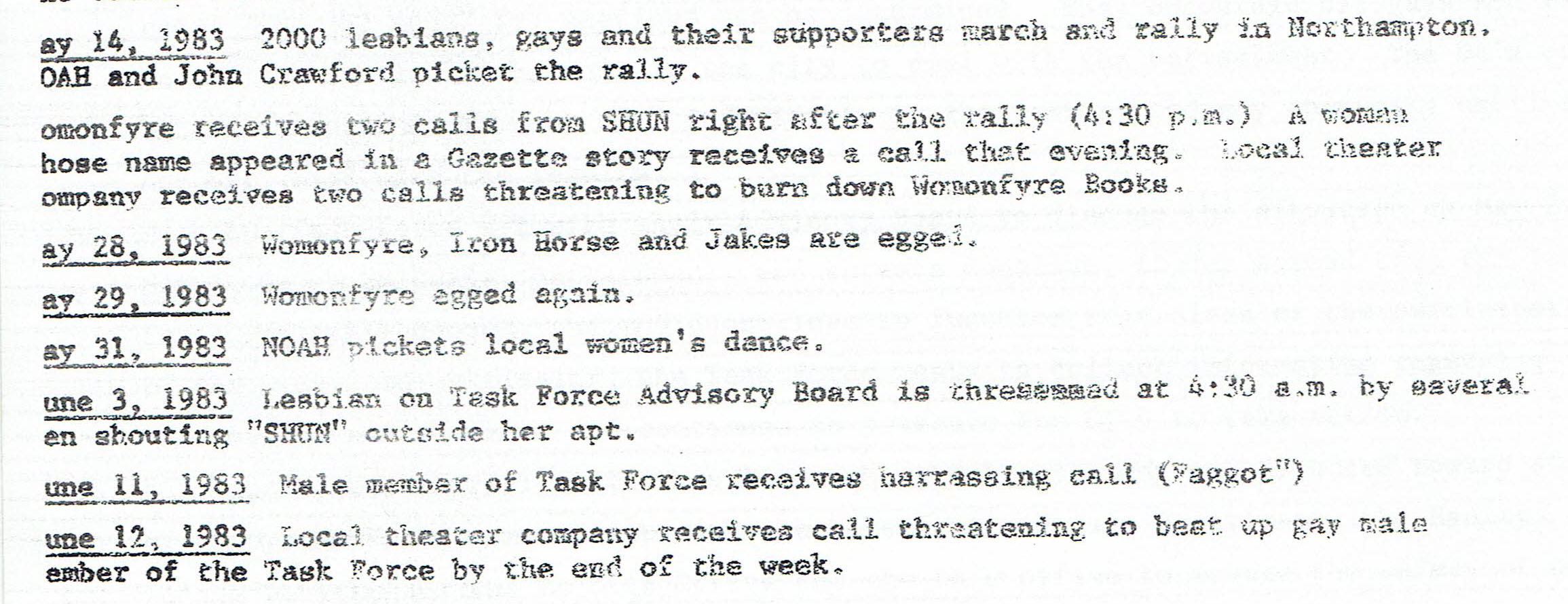

In the month following the March, ”Harassment Chronology.” Lesbian and Gay Task Force Newsletter. Northampton MA. June 1983. Courtesy of Bambi Gauthier.

In the month following the March, ”Harassment Chronology.” Lesbian and Gay Task Force Newsletter. Northampton MA. June 1983. Courtesy of Bambi Gauthier.

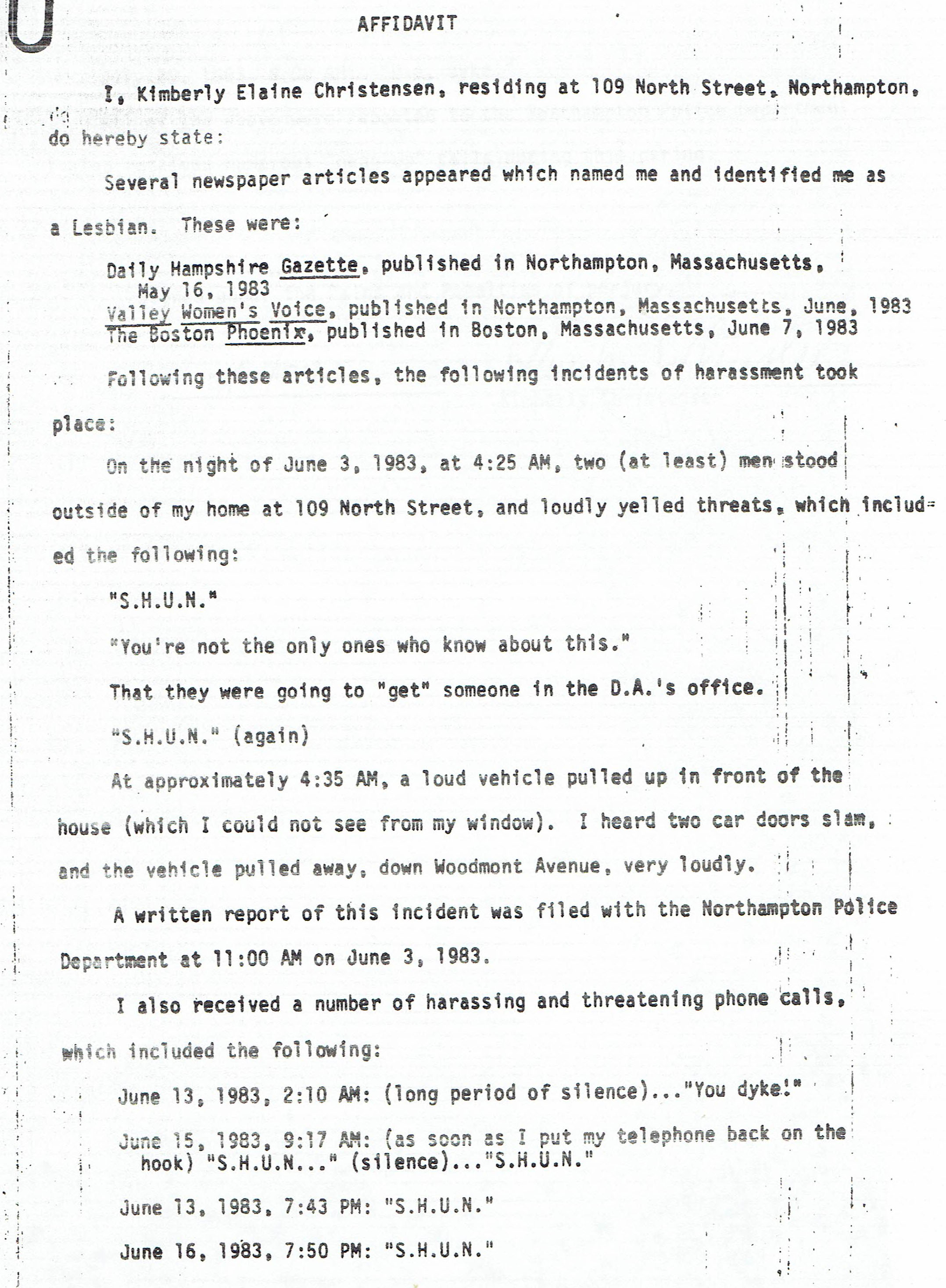

Affidavit from Kim Christensen harassment experienced by her Jun-Jul 1983.

Affidavit from Kim Christensen harassment experienced by her Jun-Jul 1983. “Harassment Reports Ignored.” Valley Women’s Voice. Northampton MA. Sep. 1983.

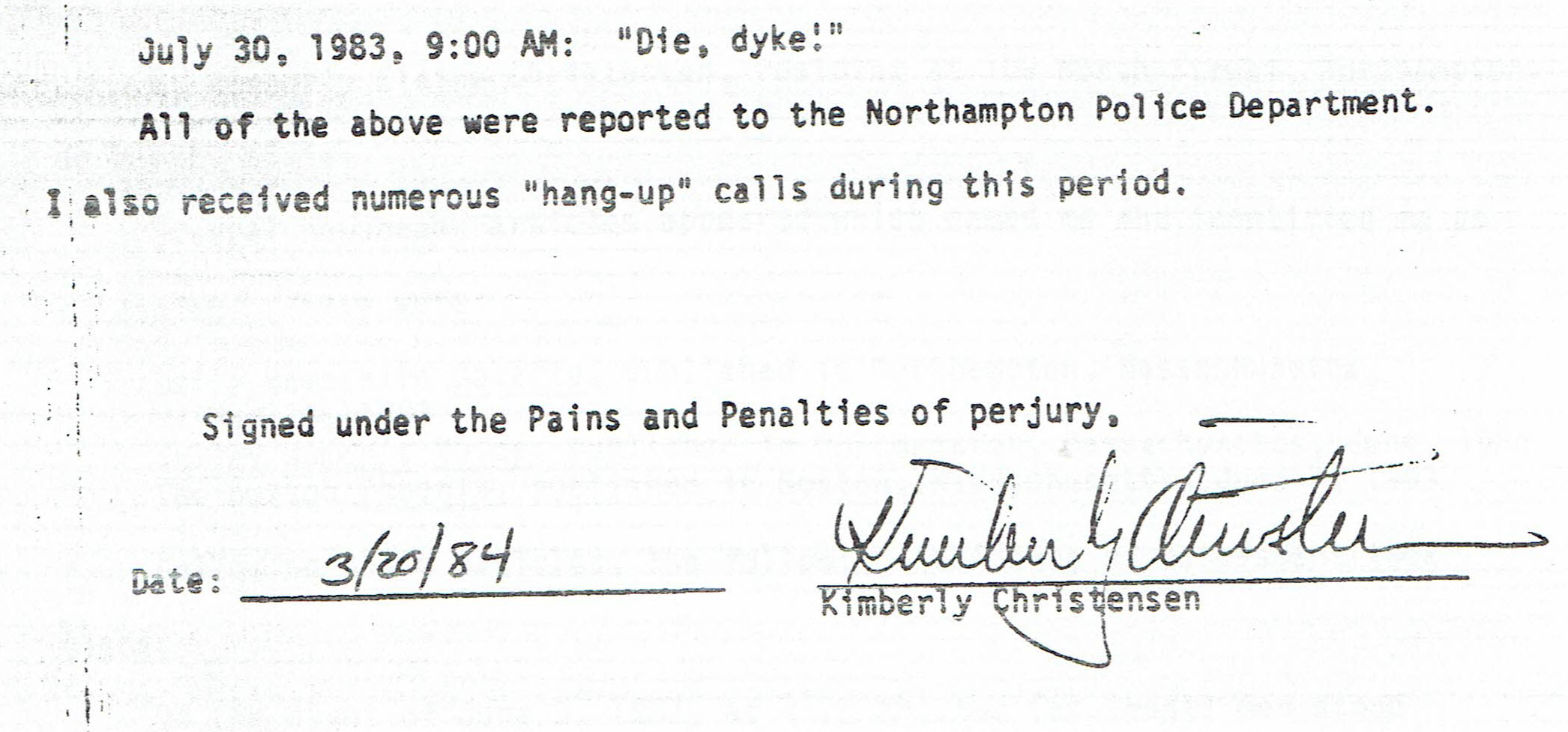

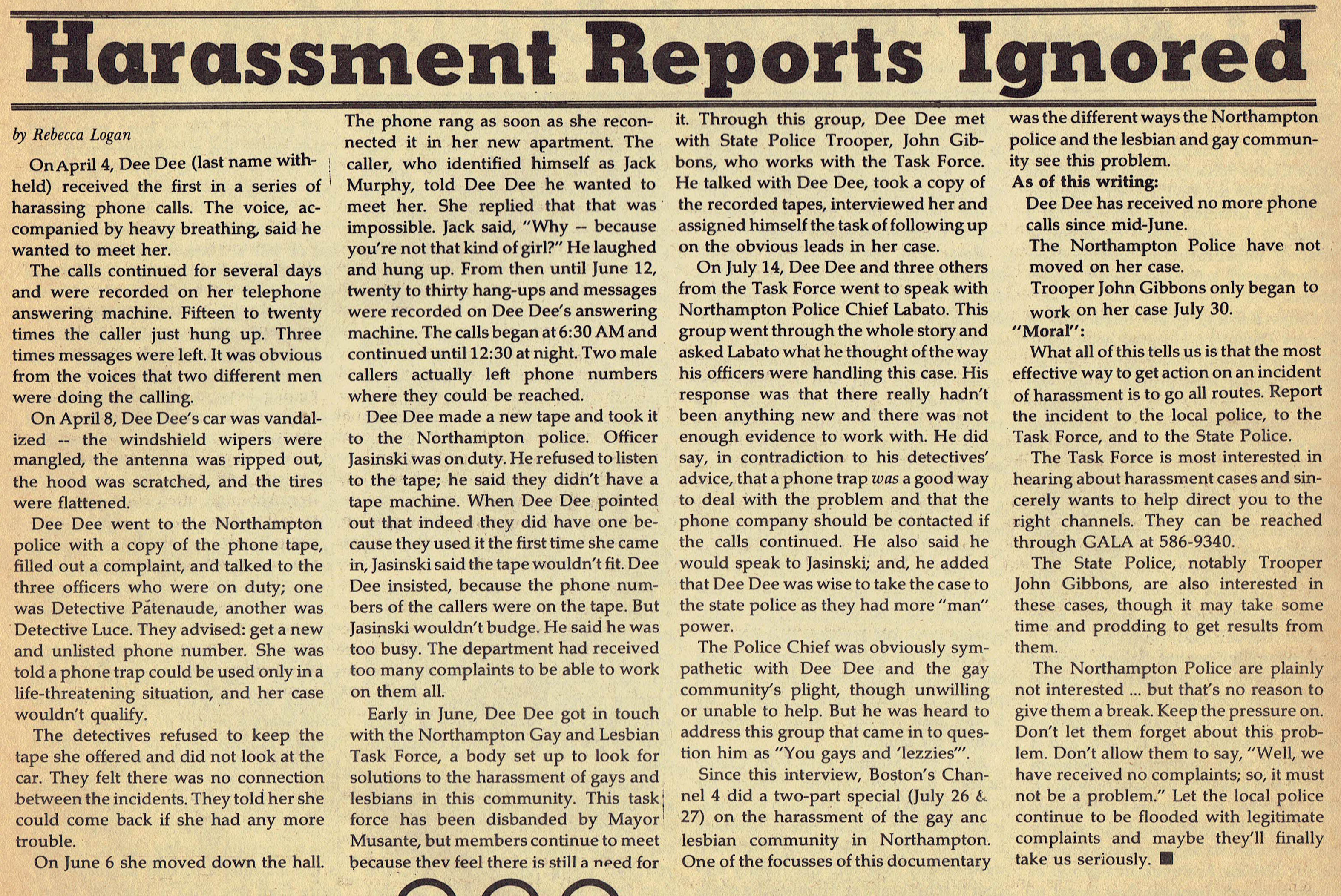

“Harassment Reports Ignored.” Valley Women’s Voice. Northampton MA. Sep. 1983. Outreach Committee, Antidiscrimination Ordinance Coalition. Letter. PVPGA Gayzette. July 1983. Courtesy of Bambi Gauthier.

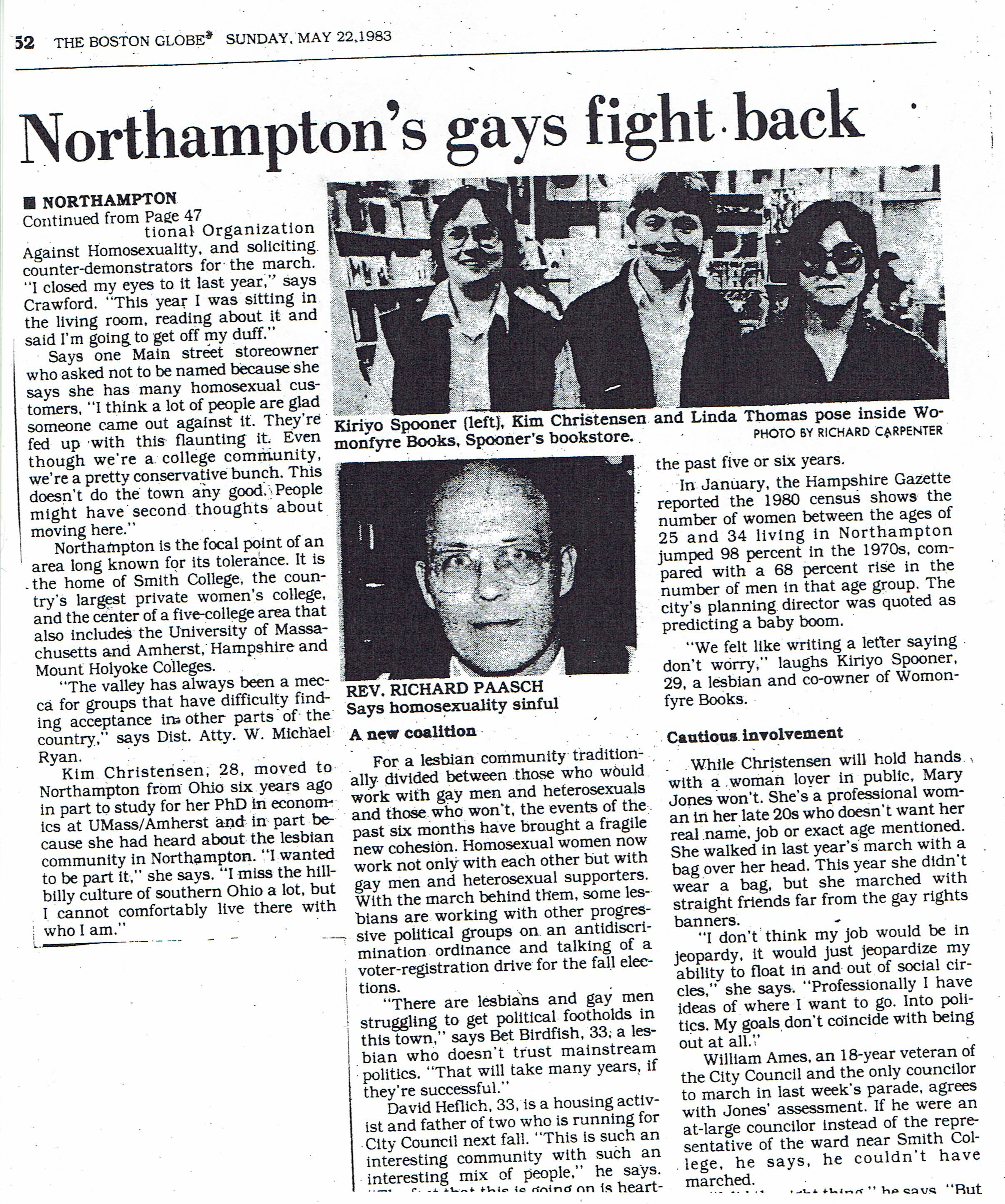

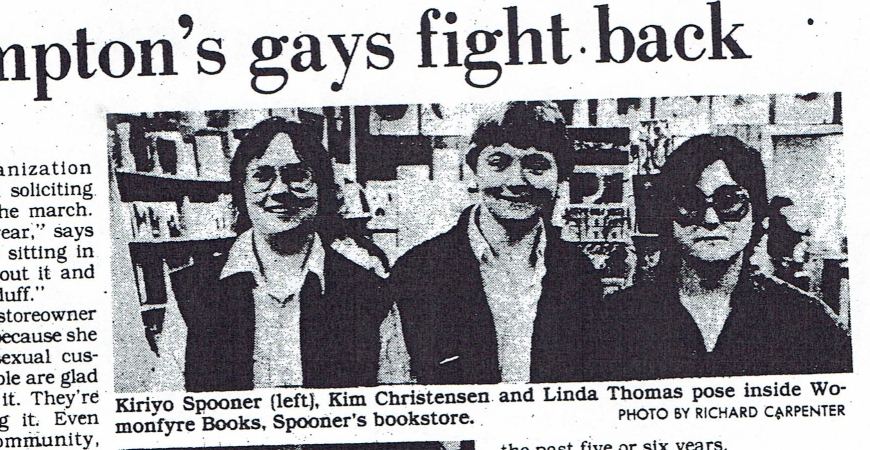

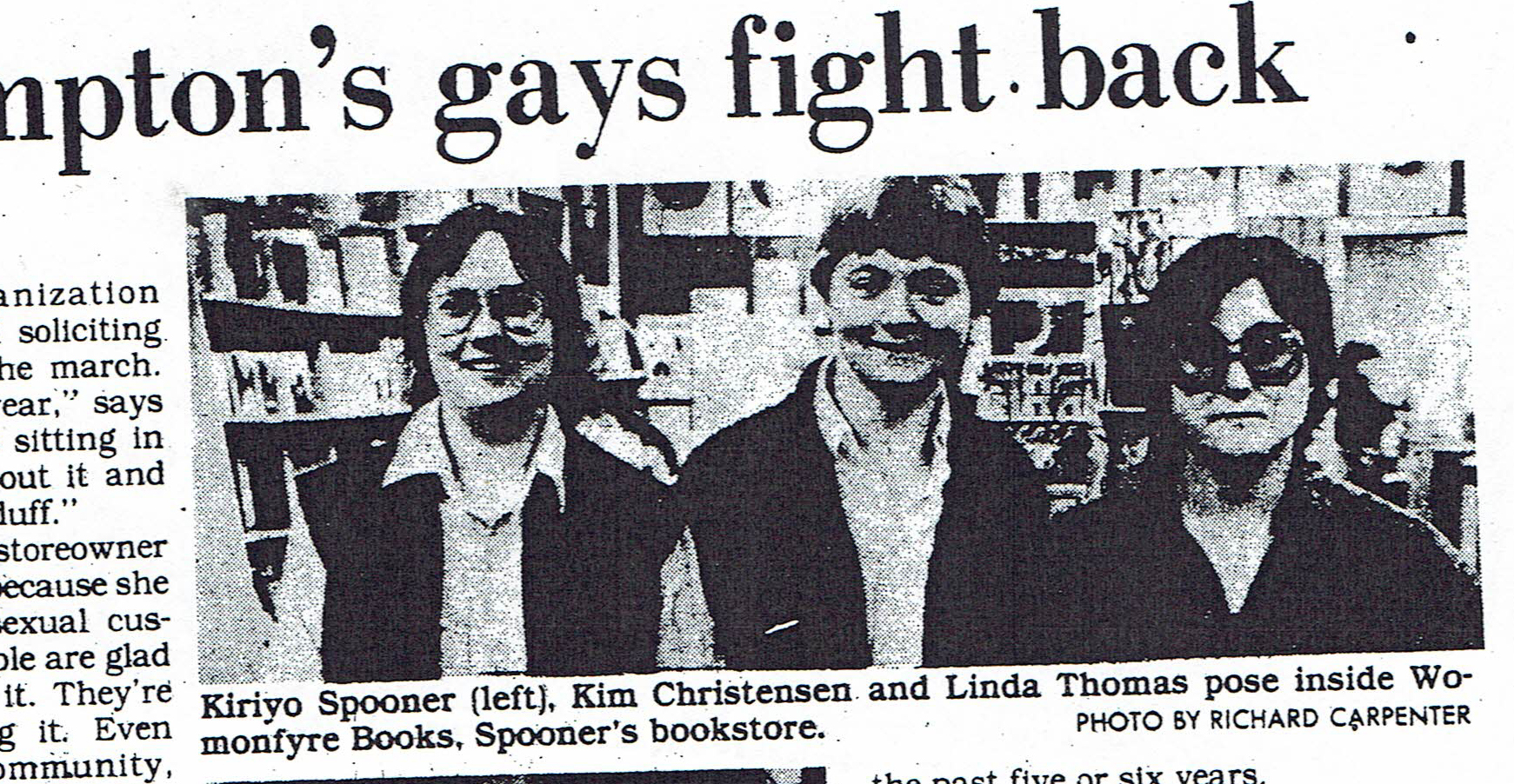

Outreach Committee, Antidiscrimination Ordinance Coalition. Letter. PVPGA Gayzette. July 1983. Courtesy of Bambi Gauthier. Two of the three women who were key to trapping one of the harassers, Kiriyo and Kim. Bookstore co-owner Jil Krolik isn’t pictured. “Northampton’s Gays Fight Back.” Boston Globe. Boston MA. May 22, 1983.

Two of the three women who were key to trapping one of the harassers, Kiriyo and Kim. Bookstore co-owner Jil Krolik isn’t pictured. “Northampton’s Gays Fight Back.” Boston Globe. Boston MA. May 22, 1983.

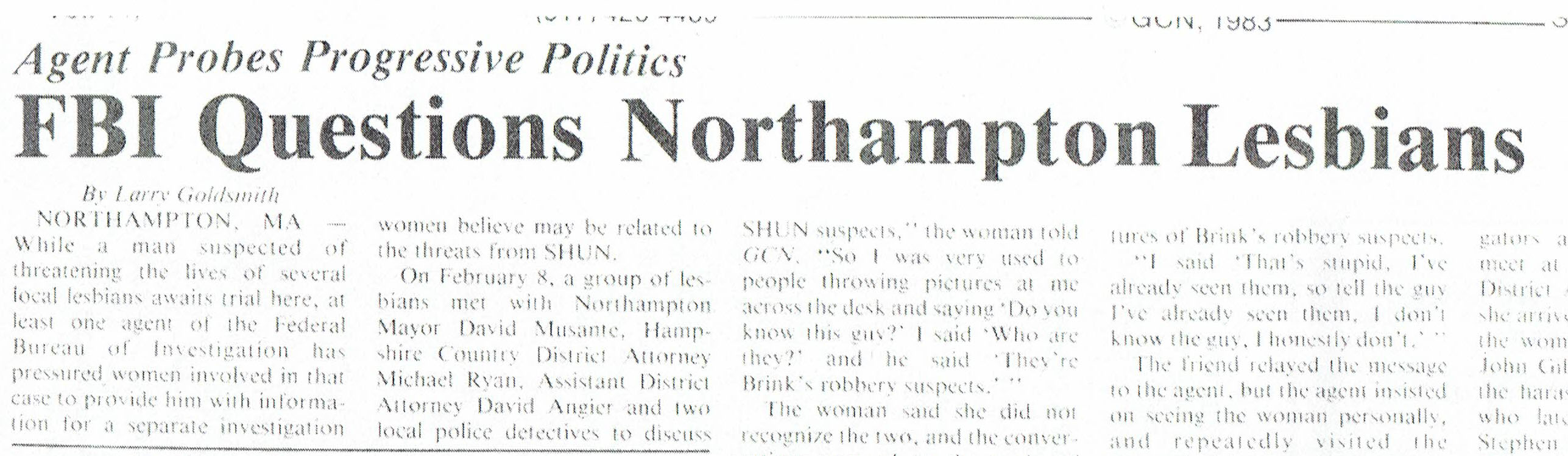

“FBI Questions Northampton Lesbians: Agent Probes Progressive Politics.” Gay Community News. Boston MA. Sep. 24, 1983. Courtesy of Bambi Gauthier.

“FBI Questions Northampton Lesbians: Agent Probes Progressive Politics.” Gay Community News. Boston MA. Sep. 24, 1983. Courtesy of Bambi Gauthier.

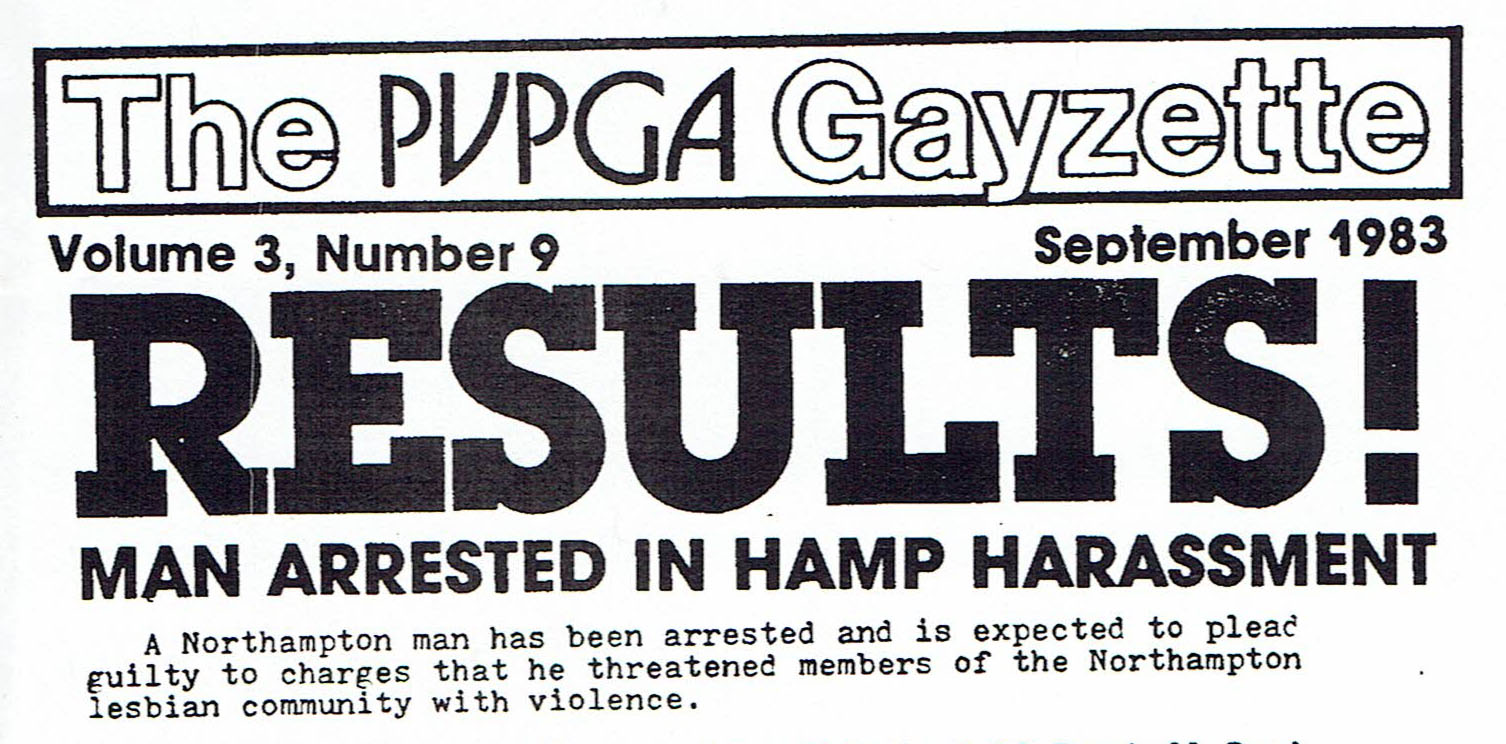

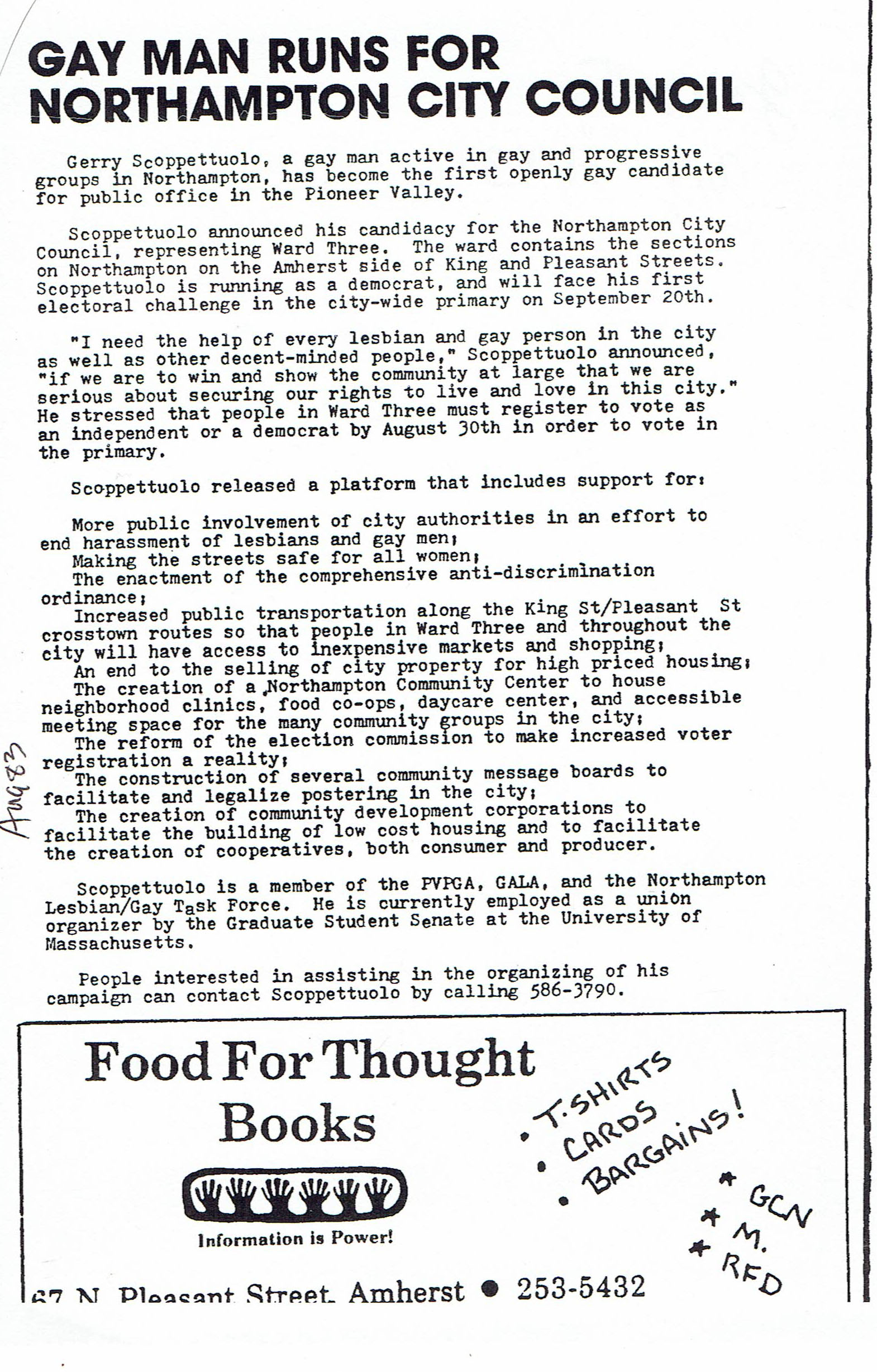

The PVPGA Gayzette. Northampton MA. Aug. 1983.

The PVPGA Gayzette. Northampton MA. Aug. 1983.

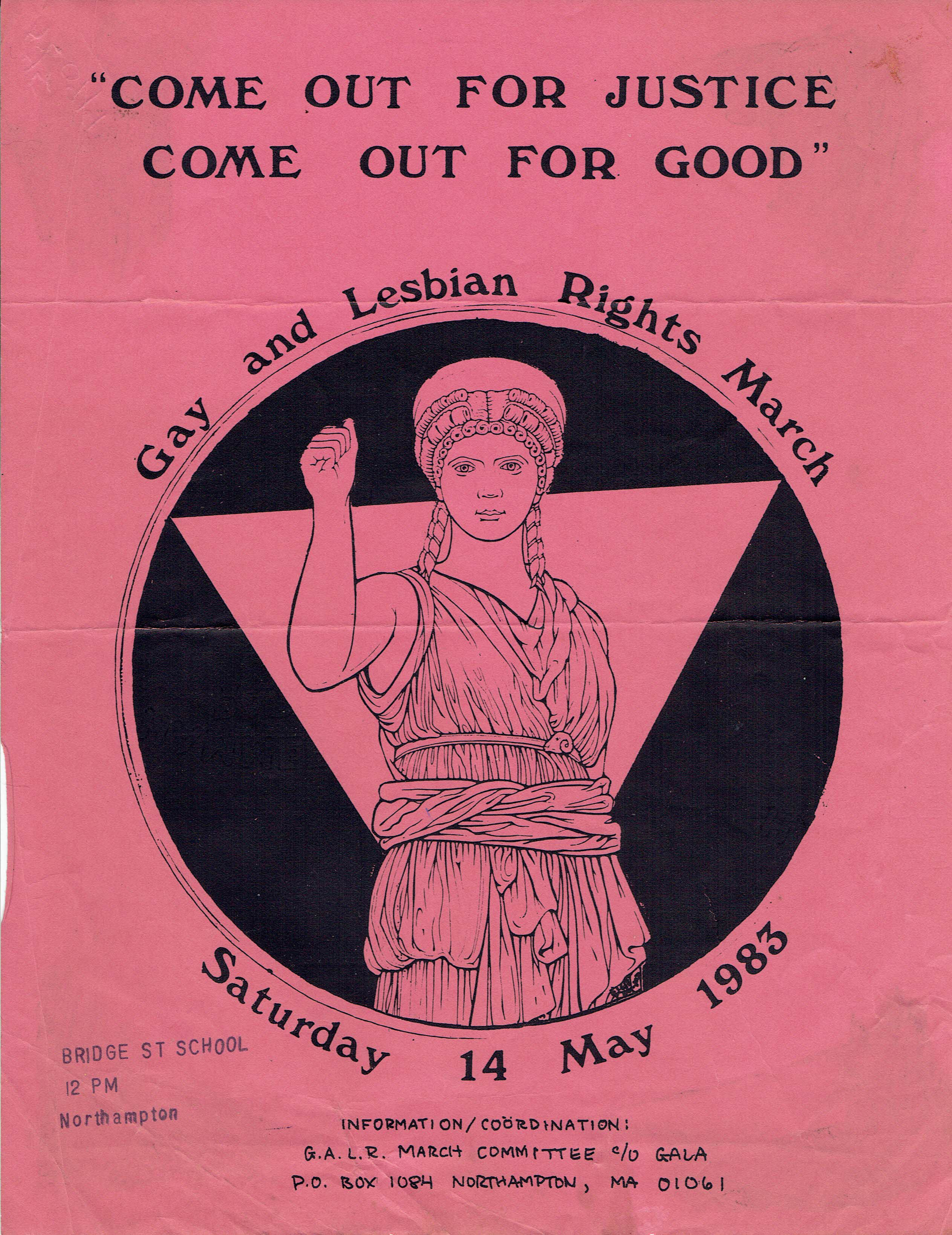

Flyer for the March. May 14, 1983. Artist Unknown.

Flyer for the March. May 14, 1983. Artist Unknown. Daily Hampshire Gazette May 13, 1983. Full page ad (here partially)

Daily Hampshire Gazette May 13, 1983. Full page ad (here partially) Log of phoned threats on GALA phone answering machine for May 9, 1983.

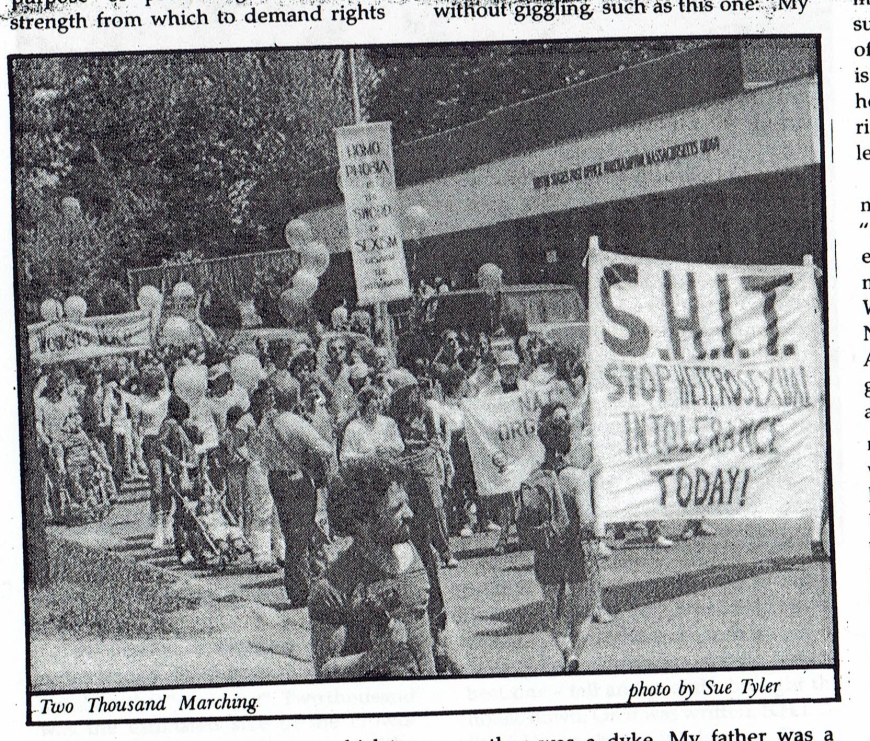

Log of phoned threats on GALA phone answering machine for May 9, 1983. Coverage of the March, Valley Women’s Voice, June 1983. Photo by Sue Tyler.

Coverage of the March, Valley Women’s Voice, June 1983. Photo by Sue Tyler. Coverage of March Gay Community News, Boston May 29, 1983

Coverage of March Gay Community News, Boston May 29, 1983